The Talented Mr. Peftiev, Part II: How Has a Notorious One-Time Weapons Trafficker from Belarus and Alleged Crony of the Country’s Authoritarian Ruler Managed to Escape US Sanctions?

If you guessed it’s because he’s a longtime CIA asset who supplied weapons for the agency’s covert operations, you hit the nail on the head.

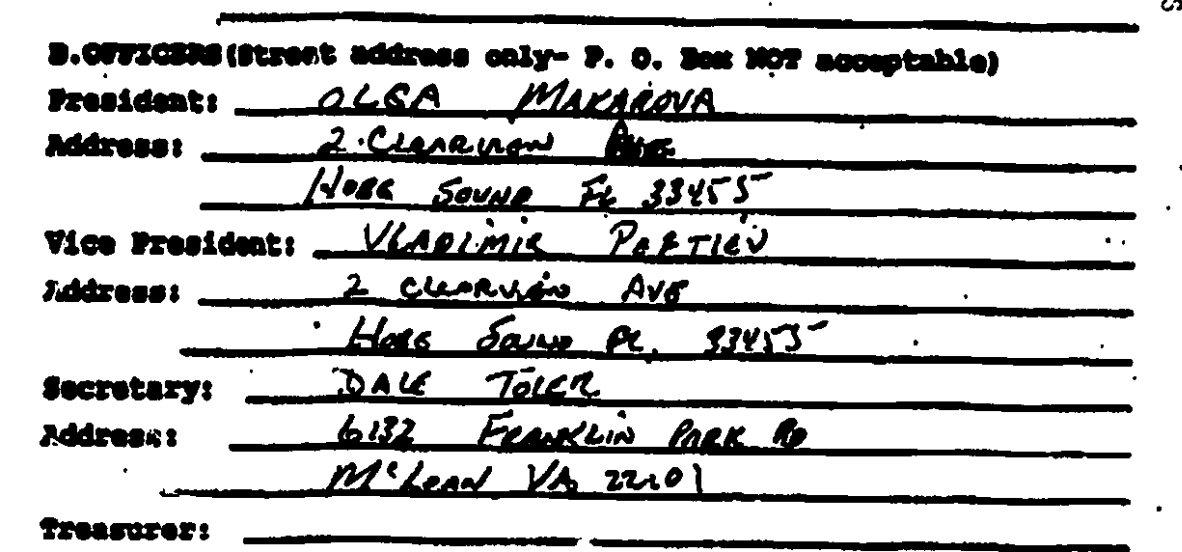

Section of a 1985 business incorporation record for LOA Investments, which was registered in Delaware and Florida, shows Belarusian weapons trafficker as company vice president and CIA-linked operative Dale Toler, a key figure in the Iraqgate scandal, as company secretary.

In Part I of this story, I recounted how Vladimir Peftiev, who became known as the “private banker” of Belarus’ authoritarian leader Alyaksandr Lukashenko, founded Minsk-based BelTekExport and turned it into a global arms supermarket. Meanwhile, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has sanctioned hundreds of Belarusians since 2020 for alleged corruption, enabling domestic political repression, and complicity in Russia’s military campaign in Ukraine. Peftiev, who’s been accused of all three, isn’t one of them.

In Part II today, I’ll conclude Peftiev’s tale by revealing his former role as a longtime asset of the CIA and other US intelligence agencies. As such, Peftiev is effectively a made man, which explains why he’s escaped sanctions thus far and will likely continue to, whether the evidence shows he belongs on OFAC’s list or not.

During the latter days of the USSR, little known Vladimir Peftiev had a management position in the Soviet military-industrial complex, but his profile rose significantly in 1993, two years after Belarus became independent, when he established the weapons exporting company BelTekExport in Minsk. By then, it subsequently emerged, Peftiev already had a seat in the inner circle of Alyaksandr Lukashenko, the unimaginative but ruthless apparatchik who won Belarus’ inaugural presidential election the following year.

Peftiev had been on the radar of US intelligence officials prior to the USSR’s collapse because he had dealings with arms traffickers who scoured the East Bloc for Soviet-made weapons they’d been tasked with secretly obtaining for the CIA and DIA. With the founding of BelTekExport, his standing soared in Washington as well, as did his role as a source of the military materiel on the combined shopping list of the Pentagon and intelligence agencies.

The CIA and DIA received lavish funding in their respective “black” budgets that was allocated to that purpose. The former sought Soviet equipment for use in covert operations and the DIA obtained it for a program called Foreign Materiel Acquisition (FMA), which reverse engineered state-of-the-art weapons manufactured by the USSR and other official enemy states and tested them against the Pentagon’s equipment in order to design effective countermeasures.

Private arms dealers – primarily European and Middle Eastern black market traffickers who were adept at covering their tracks and bribing East Bloc defense ministry officials, port employees and anyone else that needed to be greased, such as top executives at weapons exporters like BelTekExport, to take one example – were utilized to procure the desired equipment so the US government would have “plausible deniability” if a deal was exposed or otherwise bungled.

That was also the main reason the CIA supplied anti-Communist rebels it backed in the Third World with Soviet rather than US equipment, which would have been far simpler to do. The advantages of delivering Soviet arms was that it superficially obscured US fingerprints on the weapons shipments, which frequently violated US law, international sanctions, or both, and additionally veiled the unflattering fact that pro-American “freedom fighters” weren’t necessarily high-minded patriots inspired by their love of democracy, but merely CIA pets.

I first learned about US black programs that aimed to buy enemy materiel when I was researching a story that ran in Harper’s back in 2000 about Ernst Werner Glatt, who was a top supplier to both the CIA and DIA. A German ultra rightist who carried a certain nostalgia for the glory days of the Third Reich, when he was raised in the bosom of an avidly pro-Nazi family and proudly served in Hitler Youth, Glatt was not universally loved by his American handlers, who worked hard to keep his relationship with the US government under wraps, but he was so successful that those pedestrian concerns were dismissed.

The CIA and DIA maintained a stable of dozens of black market arms traffickers, some who made Glatt look like a Boy Scout, one being fellow Teuton Gerhard Mertins, who prior to his death in 1993 was another popular intermediary on deals to buy Russian weapons. Mertins was a legitimate Nazi war hero who took part in the 1943 assault led by SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny that rescued Benito Mussolini from prison after he was removed from power and detained by the Italian Grand Council of Fascism, and was active in post-war neo-Nazi organizations, as is richly detailed in surveillance reports from 1951 that were compiled by US Army Intelligence, one of the agencies that later employed him as a contractor. Around the same time, Mertins was recruited to join the Gehlen Organization, the spy network named for its founder, General Reinhard Gehlen, who headed military intelligence on the Eastern Front under der Führer and created it to gather information from behind the “Iron Curtain” at the behest of the US military, which held him custody for a short period after World War II ended.

Gerhard Mertins: Nazi war hero, future CIA employee.

Glatt, Mertins, and other arms traffickers quietly purchased materiel that ultimately found its way to the contras in Nicaragua, UNITA in Angola, and Osama bin Laden’s mujahideen forces in Afghanistan, which subsequently morphed into Al Qaeda. Intermediaries for US intelligence accomplished things that “boggles the mind," a former CIA official told me when I was researching the story about Glatt. “They were dealing with Communist officials at the highest levels and getting factory-fresh weapons out of the Eastern bloc,” said the source, who was one of numerous US officials and arms traffickers directly involved in purchasing Soviet hardware who were aware of Peftiev’s assistance in those efforts. “There was nothing money couldn't buy."

Prior to the fall of the USSR, operatives for the CIA and FMA scored their greatest successes in Poland, Bulgaria, and Ukraine. Belarus was a secondary market at the time, but that quickly changed during the post-Soviet era due to BelTekExport’s founding by Peftiev, whose accommodating manner and flexible terms endeared him to intermediaries working for the US. “Everyone was trying to operate in Belarus,” a former consultant to arms brokers who purchased goods for the FMA recently told me. “BelTekExport had items no one else had.”

As previously noted, I’m not clear on exactly how or when US intelligence operatives first came into contact with Peftiev, who I sought an interview with through Steptoe & Johnson, the Washington firm he hired in 2021 and keeps on retainer to help ensure he steers clear of OFAC’s list of sanctioned foreign nationals, but didn’t hear back from the lobby shop or their client. By early 1995, however, two years after BelTekExport opened its doors for business in Minsk, Peftiev was not merely an asset of US intelligence, but an important and trusted one.

That February, even as his weapons exporting company in Belarus was taking off, Peftiev became the vice president of a new business registered in Virginia called BelTekExport International, corporate records filed at the time show. The following month, BelTekExport International registered to operate in Florida as well.

The new company had an office on the fourth floor of a building at 1825 I Street NW, just a few blocks from the White House. Corporate records disclose no details about what type of business BelTekExport International was supposedly engaged in, but it was clearly a shell entity created to buy weapons on the black market as part of US-approved intelligence operations.

Valery Azamatov, who like Peftiev became one of the richest business officials in Belarus under Lukashenko, had the title of secretary at the company. He was described as an “investor” who made a fortune in Latvia and “likes to make black caviar in his spare time,” in a 2021 article in Intelligence Online.

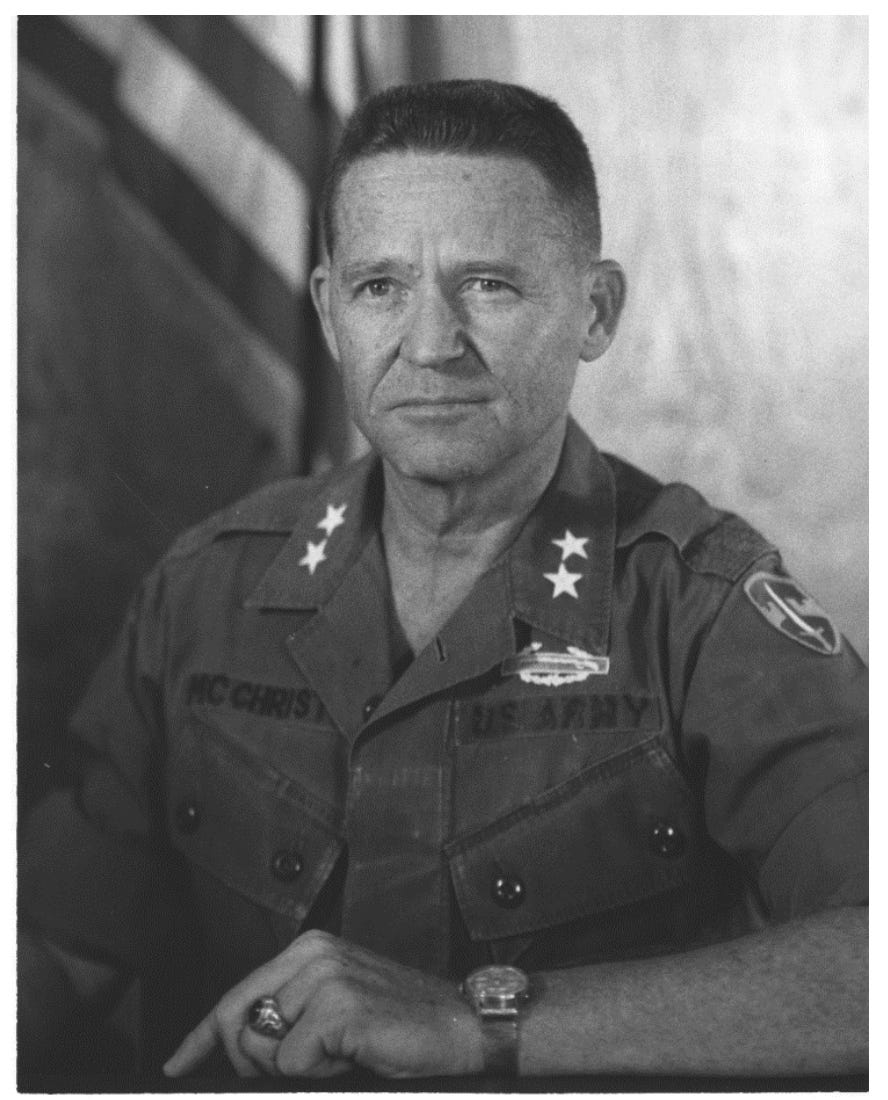

More tellingly, Joseph McChristian, a former US Army Major General who was the assistant chief of staff for intelligence to General William Westmoreland in Vietnam between 1965 and 1967, was BelTekExport International’s president and registered agent. During his time in Vietnam, McChristian built a “computerized, automated intelligence processing organization with more than 1,100 American and Republic of Vietnam staffers interrogating suspects, translating captured documents, interpreting photos and other data, processing onto IBM cards and tapes, editing, sorting, analyzing and coding every minute detail on the enemy,” a 1967 article in Army Magazine recounted.

McChristian, who after retiring from the Army in 1971 was inducted into the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame, died in 2005 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. As with many ex-military and intelligence operatives, McChristian stayed in the game after departing from public service, as seen in his collaboration with Peftiev, whatever the precise nature and activities that resulted from their “business” partnership.

US Army Major General Joseph McChristian, who build a vast interrogation network in Vietnam and was inducted into the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame before his brief collaboration with Peftiev.

BelTekExport International’s attorney Lane Gabeler also had an interesting background. A resident of McLean, Virginia, home to the CIA’s headquarters, Gabeler was “active in business and civic matters throughout her career,” according to her 2009 obituary. Based on the available evidence, she was likely engaged, officially or otherwise, in more exotic affairs along with her husband, Charles Gabeler, who delivered weapons and military goods to Vietnam and other US allies in Southeast Asia when he ran Air America for the CIA. Lawrence Devlin, CIA station chief in Congo in 1960 when the country’s first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, was overthrown and executed, met Gabeler about a decade later when he had been moved to Laos to head the agency’s operations there, and later called him an “outstanding officer” who pulled off operations no one else would even attempt.

During his CIA career Gabeler also worked in Taiwan, South America and Iran, and “worked for the agency under contract” after retiring around 1980, according to his obituary in the New York Times 18 years later. It appears certain that Lane Gabeler, who also prepared and filed corporate records for BelTekExport International, took care of routine but sensitive legal and administrative matters for the CIA, such as setting up a shell company for a colleague of her husband from the days they worked together in Vietnam and two dubious foreign oligarchs, one who then headed a major weapons exporting firm in a country that had a hostile relationship with the US.

During the seven months that followed BelTekExport International’s establishment in Virginia, Peftiev was made an officer at three other newly-registered US shell firms. Two, Ambel Corporation and Belamex Limited, were created in April 1995 in Illinois. Peftiev was named president of both firms and a man named Wesley Michalczyk, the only other person identified in the corporate paperwork, was listed as their registered agent.

Business incorporation was not Michalczyk’s main line of work, though. Born in Warsaw, he moved to the US in the 1970s and “made his first serious money there,” which he invested in coal and oil projects in post-Communist Poland, according to a February 2024 story in the Visegrád Post about “entrepreneurs” who’d emigrated when the country was part of the USSR. Michalczyk also “mediated several defense contracts...which earned him the ominous-sounding title of ‘arms dealer,’ however, the specific extent of this activity of his is not known,” the story added.

In fact, arms trafficking was apparently the primary occupation of Michalczyk, who was another of the foreign intermediaries used by the CIA and DIA to purchase Soviet hardware, which was very obviously what he and Peftiev were up to with Ambel and Belamex. Details of Michalczyk’s involvement in the weapons trade are contained in a 72-page request for legal assistance that the organized crime unit at Poland’s federal prosecutor's office sent to US law enforcement authorities in 1998, three years after the Illinois shell firms were set up.

Polish “entrepreneur” Wesley Michalczyk was wanted in his native land for arms trafficking and money laundering, but it turned out all the crimes he alleged committed were part of his CIA duties, which is almost certainly why the case against him, which Peftiev was implicated in as well, was dropped.

The request asked for evidence to support an ongoing investigation by the prosecutor’s office into illegal arms trafficking and money laundering by Michalczyk and a number of his associates, including Peftiev, Jacek Wypych, who ran BelTekExport’s Warsaw office, and Polish-born Pawel “Paul” Podedworny, a business partner of Michalczyk in another Illinois shell company called Amron Limited. The crew were suspected of laundering at least $6 million in proceeds from illegal weapons sales through a web of shell companies in Panama, Poland, England, Ireland, the British Virgin Islands, and the US, which included Amron and LOA Investments, which had received a bank wire for $25,000 it falsely labeled as payment for a computer program.

LOA was also the fourth of the US shell firms created in 1995 that Peftiev was linked to, and it was arguably the most interesting of them all. Incorporated in September of 1995 in Delaware and Florida, LOA’s president was Olga Makarova, Peftiev’s then mistress and future wife, he was the vice president, and the firm’s secretary was Dale Toler, a helicopter pilot for the Army during the Vietnam War who “continued his service to the country flying fighters with the Maryland Air National Guard,” said his 2014 obituary.

That bland summary omitted much more intriguing information about Toler, most notably that he was a long time US intelligence operative involved in a wide range of covert activities, which emerged in 1992, three years before LOA was created, when his name surfaced in the indictment of Christopher Drogoul, the central figure in the so-called Iraqgate scandal. The manager of the Atlanta branch of Italy's Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, more commonly known as BNL, Drogoul was charged with authorizing billions of dollars in secret loans to Iraq, which then-President Saddam Hussein used to buy critical military equipment that was used during the course of the 1980 to 1988 Iraq-Iran War.

Drogoul faced a prison term of up to 390 years on 60 counts of fraud and conspiracy but his attorney, Bobbie Lee Cook, mounted a spirited defense that convinced many of those who were in the courtroom at his trial, including Judge Ernest Tidwell, that his client acted with full knowledge and explicit support from the US government, which viewed Saddam as preferable to the Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran and desperately hoped to see him defeat the Islamic Republic’s troops on the battlefield. “Khomeinism was on the march at the time,” a former high-level CIA official who was with the agency at the time told me during an interview. “Saddam Hussein was a nasty dictator, but Iran was a source of radicalization throughout the Islamic world and countering it was the priority.”

A key part of Drogoul’s defense was that three prominent BNL clients had told him they worked for US intelligence and banked at the Atlanta branch because it discreetly managed highly confidential financial matters related to their government activities. Toler, the most prominent of the trio, took out loans from BNL to finance the shipment of machine tools to Iraq through a firm he controlled named RD&D International. Though Toler was never charged in the affair nor called to testify during Drogoul’s trial – for reasons that are manifestly evident – witnesses called by the defense confirmed he worked with government intelligence agencies and that the CIA covertly financed RD&D International.

Drogoul eventually pleaded guilty, but only to three charges of bank fraud and always maintained his innocence, saying he only copped a plea because his wife insisted he ″end this nightmare.″ Judge Tidwell sentenced him to 37 months in prison, far less time than what prosecutors asked for, saying that Cook’s defense of Drogoul had persuaded him that the administrations of both Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush had indeed encouraged off-the-books military support for Iraq.

Neither Peftiev nor Michalczyk or any of the other figures under investigation by the Warsaw prosecutor’s office were ever charged. I can merely speculate about the reasons for that, but the possibility that it didn't result from the CIA informing the relevant officials in Washington and Warsaw that the case should be dropped because any crimes committed by the suspects occurred while they were acting to support US national security is near zero.

Peftiev’s role as a US intelligence asset wouldn’t have included collecting intelligence about the Lukashenko regime’s goals and intentions, but been limited to the critical role he played in the sale of Russian weapons from BelTekExport’s stocks to operatives working for the DIA and CIA, a former official at the latter agency who knew of Peftiev from his time there told me. Not only would Peftiev have likely rebuffed any requests to spy on his home government, but it would have left him vulnerable to charges of treason by Lukashenko. The Belarusian president would not have been troubled by Peftiev’s Open Door policy for US operatives at BelTekExport, on the other hand, because it generated substantial revenue for the state treasury, and for Lukashenko and his close companion Peftiev, who no doubt made sure to keep his de facto boss happy by giving him a generous share of his personal profits on the weapons sales, including bribe payments.

Another former CIA official said there was virtually no chance McChristian, Toler, or attorney Lane Gabeler would have worked in any capacity with Peftiev – a top-ranking political and military figure of an “enemy state” – without explicit approval from the US government. “It’s not impossible they went rogue...but that would have been high risk,” he said. “If you get caught working with someone like Peftiev without clearing it first, you are going to prison.”

I’ve only detailed Peftiev’s early work with US intelligence in today’s article and the installment posted on Tuesday, but at least five former government officials and arms dealers I’ve spoken with over the years told me his collaborations with the US continued for many years. One of the sources, who once worked on FMA deals, said he had direct knowledge of contacts between US operatives and Peftiev until at least 2008, but he expected ties continued for at least a few years after that. “Peftiev was the key to doing business in Belarus for a long time,” said the source, who I spoke to this week. “He had to sign off on all the arrangements, including the bribes, and get any approvals that were needed in addition to his own.”

Whatever utility Peftiev once provided the US government would have largely evaporated in recent years. He officially sold his stake in BelTekExport a decade ago and even if he still has influence at the firm, as some suspect, it no longer has the type of importance it once did for national security strategists and intelligence agencies.

The CIA will always have an interest in supplying its overseas clients with foreign-made weapons that can’t be definitively traced to, or blamed on, the US government, and the DIA still manages the FMA program, though it’s been significantly reconfigured in recent years, but BelTexExport isn’t central to either. By the late-2000s, which is right around the time of Peftiev’s last known contacts with US intelligence operatives, BelTekExport had already sold off much of the most sought-after Russian materiel in its stockpiles, which is probably not a coincidence. Meanwhile, since the war between Moscow and Kiev began two years ago, many top-priority Russian-manufactured items on the DIA and CIA wish lists were captured or crashed in Ukraine, and brought to the US from there.

A sign of BelTekExport’s diminished value and overall dispensability as far as the US and its allies are concerned is that the European Union and United Kingdom sanctioned the company in 2020 and the US followed suit the following year, thereby outlawing any business between it and American companies or individuals. When it announced the step, OFAC said the company was “integral” to the national defense industry and played a direct role in managing “military-technical cooperation between Belarus and other countries.”

Peftiev has also been blacklisted by Switzerland, Canada and Ukraine for his role supporting Lukashenko by generating revenue for his regime, and Russian President Vladimir Putin by selling weapons for the war in Ukraine. He remains unsanctioned by OFAC, though, which is extremely bizarre no matter what one’s opinion of Lukashenko or Russia’s military campaign in Ukraine, or anything else that gets Belarusian government officials and citizens barred by the US government.

Decisions about who gets sanctioned by the US are largely political and overwhelmingly imposed to punish enemies and spare friends who often are far worthier targets – if the standards were remotely fair, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu would already be blacklisted for war crimes and banned from setting foot in the US; instead he was invited to address Congress – but Peftiev has been spared despite being on the wrong side of the divide, and even as OFAC continues to pile far less important historic Lukashenko cronies to its list of personas non grata.

The only plausible explanation for that is the one I proposed at the outset, namely that despite being reduced to the status of Useless Unsavory Acquaintance of a Foreign Tyrant, Peftiev’s years of faithful years of service to US intelligence, which helped make him unimaginably rich so it wasn’t much of a sacrifice, bought him eternal gratitude and protection in powerful quarters of the American political establishment.

That’s not surprising in the slightest, but it’s still fundamentally nauseating as a cornerstone principle of foreign policy and national security.

What were their better options for supplying Ukraine with needed arms? There really weren't any. Sending US guns didn't go well. They were stolen, and then what if they had kept that up? They show up in Gaza and Putin laughs all the way to the New York Times.